Why Do Shakespeare's Plays Make Great Movies? Part Three—Imagination

This is Part Three of a series. For Part One, click here; for Part Two, click here.

In Part One, we saw that Henry V's Chorus wishes that his theater, actors, and audience were better. To properly present the play's subjects, he says, he would need "A kingdom for a stage, princes to act / And monarchs to behold the swelling scene." He criticizes his theater as too small and his actors as uninspired, but though he wishes that his audience were made up of monarchs, he doesn't denigrate it. Instead he calls the spectators "gentles all," meaning that they're all ladies and gentlemen.

We might suppose that choruses, and characters who serve as choruses, always speak with this kind of courtesy, but two of Shakespeare's actually insult their audiences: the character who delivers the epilogue in Troilus and Cressida says that he will transfer his venereal diseases to the audience's many pimps and prostitutes; and the chorus of 2 Henry IV delivers a prologue implying that the audience is a mob, a "blunt monster with uncounted heads." These speeches implicate their audiences in the vices portrayed in their plays. Troilus and Cressida depicts weakness and corruption, which are well symbolized by V.D., while 2 Henry IV depicts the power of rumor, which spreads through mobs.

Henry V's prologue serves a different purpose: to inspire the audience. Though the Chorus begins by saying that the play's subjects can't be presented in this theater, halfway through his speech he makes a U-turn. The clash of kingdoms can be fully recreated, he says: "two mighty monarchies" and a "perilous narrow ocean" can appear "within the girdle of these walls," and huge armies can battle on this stage—if the spectators use their imaginations. Like Henry rallying his men in his "Once more unto the breach" and "band of brothers" speeches, the Chorus rallies the audience, urging them to marshal their "imaginary forces" (a metaphor that connects their imaginations to the armies at Agincourt). When you see an actor holding a pike, he tells them, visualize a thousand soldiers like him. When you hear an actor talk about horses, "[t]hink . . . that you see them / Printing their proud hooves i'th' receiving earth."

Let the play's words conjure images in your minds. This appeal, which could preface all of Shakespeare's plays, points to one of the main reasons why they make great movies. Other plays also make great movies, of course. Theater and cinema are closely related art forms, and the same features that make a great play—rich characters, exciting conflict, insight into life—will, with the right director and actors, make a great movie. Tennessee Williams's Streetcar Named Desire, for example, is a superb play that became a superb movie. But a play like Streetcar differs from a play like Henry V in that less of it was written to take place in the audience's imagination. In some ways, every play takes place in the audience's imagination: we imagine that we're seeing the play's characters, not actors; we imagine that the play's conflicts are real, not acted; we imagine that we're looking at real places, not stage sets. Yet when watching Streetcar, what we imagine is inspired by what we see, and though we entirely imagine offstage scenes like Stanley Kowalksi's rape of Blanche DuBois, most of their confrontation is performed onstage.

In Henry V, most of the war between France and England is created by Shakespeare's words acting on our imaginations. England's feverish preparations, its fleet crossing the turbulent Channel, its king's triumphant return—these scenes appear only in the Chorus's speeches, which also flesh out onstage scenes like the siege of Harfleur and the night before the Battle of Agincourt. Though that battle is performed onstage, one of its most memorable scenes, two dukes dying in one another's arms, takes place entirely in another duke's poetic description. Poetry and poetic prose—Henry's speech to the terrified citizens of Harfleur, a common soldier expressing his fears on the night before the Battle of Agincourt, a French herald's description of the battle's gruesome aftermath—convey images of war's cruelties and miseries better than any onstage action. The same is true of Shakespeare's other depictions of war; in Julius Caesar, for example, the speech I mentioned earlier—Antony's soliloquy over Caesar's body—conveys war's horrors, and the suffering of ordinary Romans, better than anything else in the play.

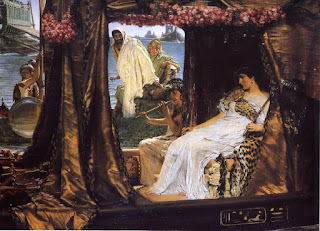

Onstage action and special effects helped Shakespeare's company create battles and other spectacles, but poetry was often more important. (By poetry, I mean both verse—rhythmic lines, rhymed or unrhymed—and image-rich prose.) Fireworks and cannon merely assisted the poetry that created the fearsome storms in Julius Caesar, King Lear, Macbeth, and The Tempest. And though the plays' royal ceremonies were created with the help of cannon, trumpets, and the costumes that were the company's most valued possessions (Henslowe paid more for a costume than for a play; together, a company's costumes were worth more than their theater), some of the plays' most spectacular ceremonies, such as Cleopatra's first meeting with Marc Antony, appeared only in poetic descriptions.

Scenes created by description rather than onstage have been cleverly dubbed "unscenes" by the literary critic Marjorie Garber (255-56). Though we might expect that unscenes would stall a play's momentum, they frequently rival onstage scenes in excitement and drama. Several of Hamlet's most memorable scenes, for example, are unscenes. An unscene begins the play's revenge plot, when the Ghost describes his murder in hallucinatory, gothic detail. Ophelia creates an unscene by describing her first meeting with the seemingly mad Hamlet, who looks "As if he had been loosed out of hell / To speak of horrors." This encounter rivals their later, onstage, "get thee to a nunnery" confrontation in tension and dramatic irony (we know what Ophelia doesn't, that Hamlet's "antic disposition" is a put-on). When Queen Gertrude describes the singing, flower-garlanded Ophelia drowning in a "weeping brook," she creates an unscene so memorable that it has inspired numerous painters—John Everett Millais and John Waterhouse are the most famous—to recreate it in fine art. And though Hamlet kills the meddling Polonius onstage, he does in the meddling Rosencrantz and Guildenstern in vivid unscenes that he describes to Horatio.

When we call Shakespeare a playwright and poet, we sometimes mean simply that he wrote both plays and poems (145 sonnets and two long narrative poems that we know of). But the plays are themselves poems, not just in the sense that they're "verse drama," meaning that parts or all of them are in verse, but in the sense that their dramatic and poetic qualities are inseparable. In performance, they combine theatrical arts—acting, effects, costumes, music—with poetry that creates images in our minds.

They thus resemble movies, which combine theatrical arts with a kind of visual poetry, with images and sequences of images on the screen. Many movie directors consider this visual poetry to be the essence of filmmaking. In an interview with François Truffaut, Alfred Hitchcock said, "When we [filmmakers] tell a story in cinema, we should resort to dialogue only when it's impossible to do otherwise. I always try to tell a story in the cinematic way, through a succession of shots." Hitchcock's is an extreme position: great dialogue, well acted, is frequently more exciting than sequences of shots, which, when overdone, can put an audience to sleep. But his view points out the visual nature of filmmaking, which would make it a poor vehicle for Shakespeare's plays—if those plays weren't poems packed with images that a creative filmmaker can render on the screen much as Millais and Waterhouse rendered them on canvas.

|

Richard Sheridan Willis as the Chorus in a 2013

Folger Theatre production of Henry V.

|

We might suppose that choruses, and characters who serve as choruses, always speak with this kind of courtesy, but two of Shakespeare's actually insult their audiences: the character who delivers the epilogue in Troilus and Cressida says that he will transfer his venereal diseases to the audience's many pimps and prostitutes; and the chorus of 2 Henry IV delivers a prologue implying that the audience is a mob, a "blunt monster with uncounted heads." These speeches implicate their audiences in the vices portrayed in their plays. Troilus and Cressida depicts weakness and corruption, which are well symbolized by V.D., while 2 Henry IV depicts the power of rumor, which spreads through mobs.

Henry V's prologue serves a different purpose: to inspire the audience. Though the Chorus begins by saying that the play's subjects can't be presented in this theater, halfway through his speech he makes a U-turn. The clash of kingdoms can be fully recreated, he says: "two mighty monarchies" and a "perilous narrow ocean" can appear "within the girdle of these walls," and huge armies can battle on this stage—if the spectators use their imaginations. Like Henry rallying his men in his "Once more unto the breach" and "band of brothers" speeches, the Chorus rallies the audience, urging them to marshal their "imaginary forces" (a metaphor that connects their imaginations to the armies at Agincourt). When you see an actor holding a pike, he tells them, visualize a thousand soldiers like him. When you hear an actor talk about horses, "[t]hink . . . that you see them / Printing their proud hooves i'th' receiving earth."

Let the play's words conjure images in your minds. This appeal, which could preface all of Shakespeare's plays, points to one of the main reasons why they make great movies. Other plays also make great movies, of course. Theater and cinema are closely related art forms, and the same features that make a great play—rich characters, exciting conflict, insight into life—will, with the right director and actors, make a great movie. Tennessee Williams's Streetcar Named Desire, for example, is a superb play that became a superb movie. But a play like Streetcar differs from a play like Henry V in that less of it was written to take place in the audience's imagination. In some ways, every play takes place in the audience's imagination: we imagine that we're seeing the play's characters, not actors; we imagine that the play's conflicts are real, not acted; we imagine that we're looking at real places, not stage sets. Yet when watching Streetcar, what we imagine is inspired by what we see, and though we entirely imagine offstage scenes like Stanley Kowalksi's rape of Blanche DuBois, most of their confrontation is performed onstage.

In Henry V, most of the war between France and England is created by Shakespeare's words acting on our imaginations. England's feverish preparations, its fleet crossing the turbulent Channel, its king's triumphant return—these scenes appear only in the Chorus's speeches, which also flesh out onstage scenes like the siege of Harfleur and the night before the Battle of Agincourt. Though that battle is performed onstage, one of its most memorable scenes, two dukes dying in one another's arms, takes place entirely in another duke's poetic description. Poetry and poetic prose—Henry's speech to the terrified citizens of Harfleur, a common soldier expressing his fears on the night before the Battle of Agincourt, a French herald's description of the battle's gruesome aftermath—convey images of war's cruelties and miseries better than any onstage action. The same is true of Shakespeare's other depictions of war; in Julius Caesar, for example, the speech I mentioned earlier—Antony's soliloquy over Caesar's body—conveys war's horrors, and the suffering of ordinary Romans, better than anything else in the play.

|

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema's The Meeting of Antony and

Cleopatra, 41 BC (1883) recreates Enobarbus's description,

in act 2, scene 2, of the Egyptian queen and her barge.

Image from Shakespeare Illustrated.

|

|

Sir John Everett Millais, Ophelia (1851-52).

|

When we call Shakespeare a playwright and poet, we sometimes mean simply that he wrote both plays and poems (145 sonnets and two long narrative poems that we know of). But the plays are themselves poems, not just in the sense that they're "verse drama," meaning that parts or all of them are in verse, but in the sense that their dramatic and poetic qualities are inseparable. In performance, they combine theatrical arts—acting, effects, costumes, music—with poetry that creates images in our minds.

|

Ophelia (Jean Simmons) drowning in

Laurence Olivier's 1948 Hamlet.

|

Comments